SILVER CREEK FIRST SETTLERS

PAGE

Readers interested in the early history of Hanover, Silver Creek and immediate surrounding country will be glad to know that THE NEWS re-prints this week the first of a series of articles that appeared under this heading in the North Chautauqua News of Silver Creek, Feb. 27, 1885. George M. Bailey, Editor and Publisher. These articles were written by Major G. L. Heaton of Silver Creek, one of our best known early citizens, and are entirely original, the material all having been drawn from original sources and written when many of the first settlers were living and the matters fresh in their memory.

Silver Creek and Hanover will always be under heavy obligation to Major Heaton for having collected, written and published this historical material. The articles originally appeared weekly for a considerable time and cover many phases of the early history. Mr. Roscoe B. Martin, who has supplied them to us, has some of Major Heaton’s manuscripts which were not included in this series. A few of these appeared some years ago in the News and others will appear from time to time in connection with this series.

The best time to preserve these papers is right now, beginning with

Article number one, as there will be no back numbers available later. Every

family should maintain a scrap book of their preservation.

The Forty and Fifty years ago columns will be continued, they having no

connection with these articles.

EARLY

HANOVER HISTORY

Founding

of Silver Creek – Early Settlers – Hardships and Privations.

A

Wedding Tour.

First

Paper.

G.

L. Heaton in the Fredonia Censor :::

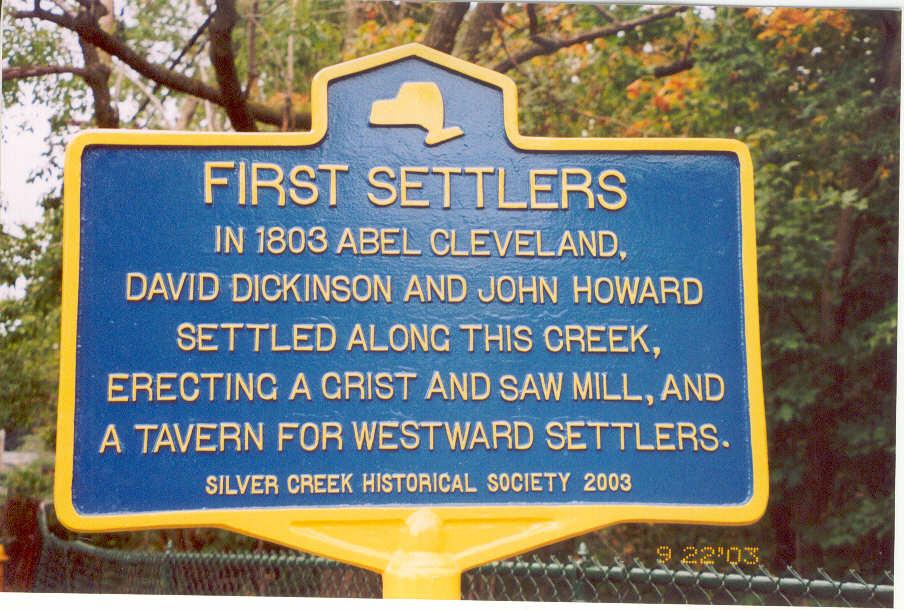

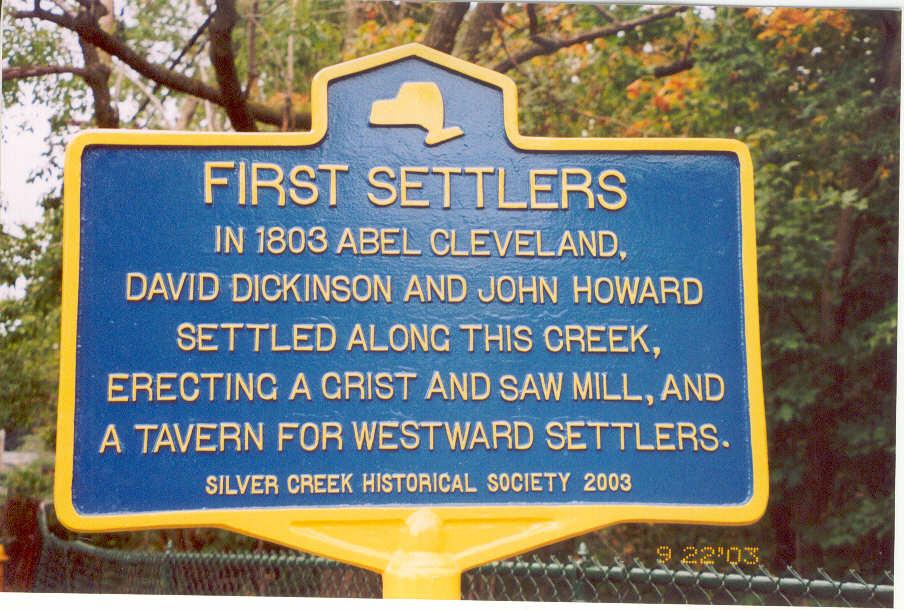

The first settlement of the part of the town of Hanover where the village of Silver Creek now stands, was made by David Dickinson, Abel Cleveland and John E. Howard, who came here with their families from Berkshire Co., Massachusetts, about the year 1802 or 1803. Dickinson and Cleveland purchased some 300 acres of the Holland Land Company, and Howard articled from the same company about 320 acres lying southwest of the land purchased by Dickinson and Cleveland. The latter track was on the northeast side of Silver Creek, bounded on the northeast by Lake Erie. All three of these parties at once commenced to erect log houses for their families. Howard’s log shanty was erected on the south bank of the creek near where Howard Street now crosses the creek. Dickinson and Cleveland erected theirs on the north side of the creek a little further down and near where the present Newbury Street now runs. As soon as their families could be made comfortable, the three men engaged in cutting off the timber and clearing up a place for planting corn and other vegetables for their subsistence. At that period there was no mill within many miles of them. Both Dickenson and Cleveland had worked a little at the milling business in Massachusetts before they left there. They very soon conceived the idea of erecting mills for the purpose of cutting out timber and converting Indian corn into meal. They knew that with the material and tools they had, their construction must be of the most crude nature. They first erected a saw mill, with which they managed to cut out lumber enough to construct the other portions of their mill. Their first process of corn into meal was done by pounding in place of grinding. This was done by making a mortar from a large maple tree or log sawed off some four or five feet long. A cavity was made in one end by boring, burning and cutting. This mortar when complete was placed on end and from a peck to half a bushel of shelled corn was put into it at a time and it was so arranged that when their water wheel was started and the pestle worked up and down with force enough to mash the corn and convert it into meal. However previous to their getting this machine into operation, Mr. Howard and his oldest boy, Jay, then a lad of 13 years of age, had built a skiff or light row boat from some basswood boards cut out in Dickinson & Cleveland’s saw mill and with Dickinson started with some ten bushels of corn they purchased at Batavia while on their way to their new home, for a mill at Chippewa, a small place about 20 miles down the Niagara River. At that time this mill at Chippewa, if not the nearest, was the most accessible for they could get to that by water, but this trip to mill came near being disastrous to the young colony. At the time they left home they expected to be able to make the trip in five or six days but on account of the wind storms they encountered on their way down and returning, they were greatly delayed. On the evening of the first day they reached the mouth of Eighteen Mile Creek, where they determined to go into camp for the night. They had scarcely got their camp fire well started, and their boat securely taken care of, when a terrific thunder storm accompanied by a severe gale of wind came up. They were compelled to remain there thirty-six hours, before they could proceed; they finally reached Chippewa, and then at the end of twenty four hours had their ten bushels of corn ground into meal, and were ready to start on their way back. They again encountered a rain storm at Buffalo and came near losing their meal by getting it wet. They were again compelled to remain over thirty-six hours at Buffalo, but improved the time by making some purchases of necessary supplies at a log store or Indian trader’s that stood near the site of the present Mansion House. The prices that goods sold for at that time would astonish the merchants of today. Ordinary brown sugar was regarded cheap at twenty-five to thirty cents a pound. A very common grade of Bohea tea could be had at $1.50 per pound. Common factory shirting was then termed sold at 35 cents to 40 cents, whiled calicos brought from 40 cents to 50 cents a yard. It was on the morning of the 12th of September they left Buffalo, hoping they would have good weather and be able to reach home by daylight the next day. They proceeded but a few miles before the wind commenced blowing from the southwest and increased to the extent that when a short distance from Hamburg, they deemed it for their safety to make for the shore. By keeping a good look-out they discovered a place where they thought it would be safe to attempt a landing. This was accomplished and after carrying their meal and other stores to a safe, dry spot on shore, they drew their boat up and prepared to wait until the wind decreased so that it would be safe for them to proceed. The wind died away with the sun but the sea did not run down so that it was advisable to start until near daylight next morning. Notwithstanding they had had considerable head wind, they were able to continue on their journey all the next day, and reached the mouth of Silver Creek soon after sunrise on the twelfth day after leaving home. Cleveland, who remained at home to look after the welfare of the women and children, was glad enough to welcome them back. He had become seriously excited over their long absence, and had fears that they and their cargo had been swamped and would never be heard of again. Soon after Dickinson and Cleveland had their mortar in operation, they dug from what is now known as Oak Hill, a couple of boulders which they succeeded into working into a mill stone, that answered a very good purpose for grinding corn. As soon as it became a settled fact that there was to be a war between the United Stated and Great Britain, Dickinson and Cleveland sold their property and returned to Massachusetts. They did not care to remain so near the lines. Howard improved all of his spare time in cutting down all of the hemlock trees, which were found of immense size all over the ground where the village now stands, and cutting them into logs which he hauled to Dickinson Cleveland’s mill and had them sawed into two-inch planks. With these he constructed the first frame house build in the town of Hanover. This building would hardly be termed a frame house at this period. It was erected on the grounds where the Eureka Smut works now stands. The site offered an opportunity of a basement or lower story which could be entered from the east side of the building. The planks were set perpendicular and pinned with one and one-fourth inch wooden pins at the bottom to hewn sills and at the top to plates that supported the rafters. The roof was composed of staves riven from hemlock and ash trees. They were held to their places by long poles or saplings running longitudinally with the building. These were also joined to the rafters. The floors were made of rough boards which were held down by wooden pins. There was probably not twenty pounds of nails used in the construction of the entire building. In the spring of 1805, Mr. Howard opened this house as an inn or house of entertainment for the accommodation of travelers, and continued it as such until 1828, when the property passed into the hands of the late Oliver Lee. For many years previous to and after the war of 1812 with Great Britain, Howard’s Tavern was one of the most popular stopping places for travelers and immigrants between Buffalo and Erie, Pa. Soon after the close of the war there was a large emigration from the New England States to Northern Ohio, Then known as New Connicutt, and later as the Western Reserve. At the commencement of the colony here, there was but little more than a bridle path from Buffalo west. In fact, loaded teams were compelled to make much of the distance along the edge of the lake, sometimes in the water until it nearly came into the wagon boxes, and during heavy storms in the spring and fall they were compelled to lay over until the storms abated. About the year 1812 the Holland Land Company had caused a road to be surveyed from a point in the town of Hamburg about eight miles from Buffalo through to the Pennsylvania state line. Eight miles west of Buffalo through to Buffalo had to be made along the beach of the lake through the sand and it was regarded as a good day’s work for a heavily-loaded team to make the distance to the beach, as it was termed. The country for some distance back from the lake was low and swampy to that extent that it was regarded as almost impossible to construct a road through it, and it was not until 1832 or 1833, that a charter was obtained from the state for the purpose of building a turnpike through this swamp. It was nearly a year after the survey of the Holland Land Company before much if anything was accomplished in cutting the road through. At the time there were but very few settlers between this village and Buffalo and it was no great object to those few to do any more labor upon the roads than they were compelled to do or were well paid for doing. It was no unusual thing for heavy emigrant teams to be three or four days making the distance from Buffalo to Silver Creek. They usually traveled in companies of four or five or six teams together and often were compelled to double their teams and haul one wagon a mile or so over a bad portion of the road, the go back for another, and in this way make half the distance from Buffalo Creek here, and it was not unusual for teams to remain two nights in succession in the same place, that is, they would not get so far in a day, but they could return to the place where they had spent the night efore[1] for entertainment. Emigrants from New England to the Western Reserve felt, when they reached this point that the principal part of their trouble and hardships were over and on reaching here they would often spend two or three days with Mr. Howard recuperating their animals and repairing their wagons. In those early days there was many a joke got off at the expense of the almost bottom-less roads through the Cattaraugus Swamp. It was said that on one occasion a company of three or four foot travelers were picking their way along the so-called road two or three miles east of Cattaraugus Creek, when they came to a large expanse of mud water eight or ten rods in length, near the middle of which they saw a man’s head with mouth and chin barely above the water. One of the party sang out to him and asked him what he was doing there and why he did not come out. The man replied that he thought he would come out all right after a while as he had a good horse under him. But to lay jokin aside, some of the mud holes that it was impossible to avoid where of that depth that the water would come into the wagon boxes. A year or so after John E. Howard opened his house of entertainment; a Mr. G. W. Sidney opened a similar place at near the mouth of Cattaraugus Creek and established a ferry across the creek which was of great advantage to travelers. Sidney kept his place but about a year. John Mack with his family of two sons, James E., and John Mack, Jr. came from New Hampshire and purchased all Sidney’s interest in the property. About this time, (the year 1805) there were several families settled in the northern part of the town. Among them, Benj. Kenyon and Charles Avery. A son of the latter is still living, and resides at Niagara Falls, and from him we have obtained much information. Two or three years later came Henry Ruben, Nathan and Samuel Nevins, all who came from western Massachusetts. As near as we can ascertain, Samuel Nevins was the first male school teacher this section of the town had. A school was established in the summer of 1812 and the winter following. Nevins was employed to teach it. In 1809, Artemus Clothier and Norman Spink, two young men, found their way here and engaged in cutting timber and clearing land for John E. Howard. Mr. Spink informed us but a few months before his death which we believe occurred in 1872, that during the first six months they were here they worked for Mr. Howard for $10 per month and board, and through the winter they were in the woods with their axes and ready to commence work as soon as it was light enough to do so. The following spring each of them took a contract from Mr. Howard to clear the land suitable for the first crop at a stated price per acre and the ashes accruing from the burning timber was also to be theirs. Mr. Spink informed us that during the winter it was his custom to chop through the day and just before nightfall, gather a quantity of dry bark or other dry material and start a large fire. He would the build a house or shelter of hemlock boughs, would then continue to chop by the light of his brush fire until he felt the need of rest, and would then replenish his fire with brush and logs so that it would continue through the night and retire to his bough house and bed of hemlock leaves. He also informed us that his food through the winter consisted principally of cold roast or boiled pork and cold corn bread and occasionally a potato or two roasted in the fire of one of his big log piles. Spink and Clothier followed this land clearing until they had money sufficient to locate and article a farm each for themselves.